"The nineties were better than the eighties, and one key reason was that there was less originality. Originality is unmusical. The urge to do music is an admiring emulation of music one loves; the urge toward originality happens under threat that the music that sounds good to you somehow isn't good enough."

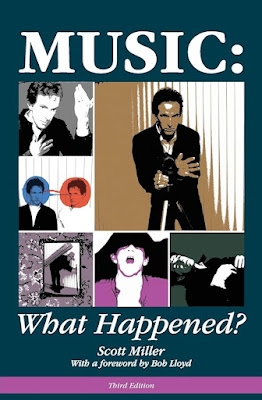

Scott Miller, Music: What Happened?

A clever thought - inspired by a song by Smashing Pumpkins of all things ("Cherub Rock")

Elsewhere, he picks up the theme:

"As you know, I kid the 1980s. I wonder can it possibly be fair to condemn an entire decade as a horrifying decline in every kind of musical competency, but nostalgia for the Eighties baffles me. Eighties nostalgia has lowered my opinion of nostalgia. So you're right, I was unconsciously targeting that kind of decline with "What Happened?" But pop music is great in that a true decline fosters a true pop response, like R.E.M. Eighties music suffered from a coliseum spectacle mentality, and R.E.M. reached around that with a sort of small-combo, home-spun literary connection approach."

Music: What Happened? - well, it's a view of music very different from mine... we do converge on early R.E.M., but it's a rare occurrence in Scott Miller's year-by-year inventory + commentary on the best best songs between 1960 and the end of the 2000s. (He carried on commenting on the year's output online, until his tragic too-early death in 2013). Even when his approbation lands on a band I love, he often picks a song by them I don't rate or actively dislike.

But it's a wonderful book to read for that very reason - full of unexpected insights and precision description of a song's moving parts, informed by his being a musician (Game Theory, The Loud Family) and operator in a scene (loosely, college rock) that had its own distinct metric of evaluation (craft, structure, daintiness to a degree.... cleverness as a pure value... melody above all, but understood in a particular sense, that sense defined by the inside-out - in my view - position that the tunes of Grant Hart were better than the tunes of Bob Mould).

So yes the '80s canon is dBs, Let's Active, XTC, the bleedin' Smithereens... and by the '90s (The Posies, Jellyfish, They Might Be Giants) it's getting even further from both my own aberrant pantheon and the mass idea of what pop is.... by the 2000s, it's beyond marginal.

But Music: What Happened? - despite the implied, "it all went to shit" in that title - reads neither as contrarian nor embittered, but as simply the eloquent expression of another way of listening, another kind of loving.

Here's a review by Michaelangelo Matos that goes into Miller's methodology in the book (each year's harvest relates to a CD comp of his favorite tunes released that year).

A playlist of damn near every song that makes up Miller's personal pantheon

And one that goes from 1980 to when he left off in the early 2010s - what you might call A College Rock Canon

Interview with Scott by Matthew Perpetua.

There's a bit in it riffing off the Smashing Pumpkins / originality comments: